Recovery audit contractors: The age of audits and remediation

The age of audits and remediation

By Kate Alfano

It’s a fact of medical practice that despite the best intentions, a physician who does not know how to correctly code for his or her services—or employ someone who does—will not stay in business for long. To be paid, physicians must reduce the complex art of medicine, their covenant with their patient, into a diagnosis, a procedure, a visit, a number.

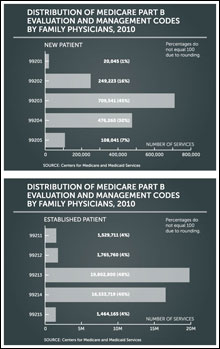

It is also generally understood that claims for evaluation and management services, the most common code set billed by family physicians, have high error rates because of their subjectivity. Of the more than 1 billion claims submitted in 2010 by more than 1 million Medicare providers, 43 million were E/M claims for new or established patients. And as Medicare consumes an increasing amount of federal spending—13 percent in 2010, or $452 billion—it’s no surprise that lawmakers, economists, and policy wonks would look to billing and coding for ways to reduce fraud, waste, and incorrect payments.

Enter the recovery audit contractors, bounty hunters tasked with identifying “improper payments” submitted by any entity that bills Medicare Parts A and B, collecting overpayments, settling underpayments, and implementing actions to prevent future errors.

Overpayments occur when a physician bills for an incorrect payment amount, perhaps through an outdated fee schedule; incorrectly codes; bills for non-covered services; or bills for duplicate services. AAFP says the RACs are homing in on consultations, E/M services provided on the same date as a procedure, E/M services provided during global periods, and relationships between physicians certifying durable medical equipment and suppliers of the equipment.

The most common underpayment occurs when a physician submits a claim for a simple procedure when the medical record reveals that a more complicated procedure was performed, says Bradley Reiner, owner of Reiner Consulting and Associates and practice management consultant for TAFP.

The national RAC program as it stands is built on the foundation of a three-year demonstration that used contractors in six states—California, Florida, New York, Massachusetts, South Carolina, and Arizona—to detect and correct improper payments and to determine whether the use of third-party entities would be a cost-effective means of ensuring correct payments. From 2005 through 2008, they collected nearly $1 billion in overpayments and repaid $37.8 million in underpayments. The RACs referred only two cases of potential fraud to CMS, though they did not receive payments for those referrals.

CMS awarded contracts to four private entities in 2008 to become the permanent recovery audit contractors. Atlanta-based Connolly Healthcare won the contract for the largest region, Region C, which encompasses 15 states, including Texas, and two territories.

The recovery auditors are paid a contingency fee for what they find based on their original bid to CMS, hence their notoriety among critics. Connolly’s is the lowest of the four regions at 9 percent; the highest, Region B, is 12.5 percent. An exception is the recovery of overpayments for durable medical equipment claims, which garners a fee of 14 percent for Connolly and 17.5 percent for Region B. CMS requires RACs to return the contingency fee if their claim determination is overturned at any point in the appeal process.

So far, from October 2009 through December 2011, the RAC program has identified $1.45 billion in improper payments nationwide. Of this, $1.27 billion were overpayments collected and $183.7 million were underpayments corrected. Under the RAC demonstration program, approximately 96 percent of identified improper payments were overpayments. In the permanent program, 88 percent have been overpayments.

CMS posts the most frequent types of issues undergoing review each quarter, and Connolly is required to maintain a list of all CMS-approved audit issues on their website, www.connolly.com. The top issue for Region C in the last quarter of 2011 was the medical necessity of neurological disorder in the inpatient hospital setting, ensuring medical documentation supported all billed services.

The RACs are required to employ a full-time physician medical director to oversee the medical record review process; assist, upon request, nurses and therapists with medical necessity reviews and certified medical coders with coding reviews; manage quality assurance; and maintain relationships with provider associations. Representatives from Connolly declined to be interviewed for this article.

Audit staff conduct two types of reviews: automated and complex. Automated reviews analyze claims data in situations where there is certainty that the claim contains an overpayment. Complex reviews use human reviewers to look through medical records when there is a high degree of probability but not certainty that an overpayment exists. All reviews are conducted on a post-payment basis limited to three years after the claim was initially paid.

The number of records the RAC can request is based on the size of the practice: ranging from 10 medical records per 45 days for a solo practice to up to 50 medical records per 45 days per physician in a large group practice. For audits that require medical documentation, Connolly accepts electronic transmissions through a secure transfer system, via CD or DVD, or by mailed paper copies.

With some exceptions, the audit contractor must complete the complex review within 60 days of receiving the medical record documentation. The results are communicated to the practice by letter with details on which coverage, coding, or payment policy or article was violated if an improper payment was identified for each claim reviewed, or if no improper payment was identified.

Cindy Hughes, former coding and compliance specialist for the American Academy of Family Physicians, says that most RAC audits of physicians do not involve a request for medical records. “Rather, the audit contractor reviews claims data and notes an aberrancy—such as too many units billed for injectable drugs—and generates a demand for a refund of payments related to the number of units above a standard or medically likely dose.”

Starting Jan. 3, the issuance of demand letters became the responsibility of the Medicare contractor that paid the claims, not the RAC. The RAC submits claim adjustments to the physician’s Medicare contractor—which in Texas is Trailblazer Health Enterprises. Then the MAC performs the adjustment based on the RAC review, issues an automated demand letter to the physician, and follows the process to recover any overpayment from the physician. The MAC is responsible for answering any administrative concerns such as the time frame of payment recovery or the appeals process. Specific audit questions, however, such as the rationale for identifying the potential improper payment, should be directed to the RAC.

If the physician receives the demand letter, in an automated review, or a review-results letter, in a complex review, and disagrees and wishes to challenge the results, he or she can initiate a discussion period or an appeal.

The discussion period offers the opportunity for the physician or practice to provide additional information to the RAC to indicate why overpayment should not be collected, and it offers the RAC the opportunity to explain the rationale for the overpayment decision. The practice must initiate a discussion period with the RAC within 40 days of receipt. After reviewing the additional documentation, the RAC can reverse the decision.

The discussion period is not an appeal, nor does it remove the right of the physician to ask for an appeal. It also does not pause the 30-day time period in which the practice may ask for a redetermination, the first level of appeal. The redetermination and appeal are filed with the MAC, and the practice must file the full appeal request within 120 days of receipt of the letter.

If the practice agrees with the RAC review, the physician or physicians may pay by check, allow recoupment from future payments, or request or apply for an extended payment plan. They may also initiate a rebuttal process with the MAC by providing a statement and accompanying evidence indicating why the overpayment action will cause a financial hardship and should not be collected. The rebuttal is not used to review medical documentation or dispute the review, and it must be initiated within 15 days of receipt of the letter.

To minimize the risk of an audit, Hughes recommends that physicians implement a practice code of conduct; require annual compliance training including HIPAA, OSHA, state regulations, and billing and coding compliance; employ a documentation system that requires all staff to sign and date medical record entries; and establish procedures for billing and coding staff to question physicians about appropriate coding or missing documentation when necessary.

She advises physicians or a designated compliance officer to make sure documentation is clear and complete for all services, learn the appeal process, track denied claims and correct previous errors, and determine what corrective actions need to be taken to ensure compliance with Medicare’s requirements to avoid submitting inaccurate claims in the future.

Practice managers and staff must be trained to recognize and promptly respond to RAC audit letters, medical records requests, or requests from other program integrity contractors. A staff person who is responsible for reviewing denied claims and the reasons for denial should determine the proper course of action, whether refund, rebuttal, or appeal, and should continually monitor current RAC issues posted on the RAC website and the educational and payment policy information from local payers.

Reiner agrees with Hughes, recommending that physicians stay up-to-date on what types of improper payments have been made in their RAC region. Physicians should regularly self-audit or employ a third-party auditor to examine patterns of denied claims, and should ensure physicians and their staffs are trained on and fully understand the 1995 or 1997 Documentation Guidelines, which are available on CMS’ website at www.cms.gov.

Whether discovered through a RAC audit or any other reason, Hughes advises physicians to investigate any pattern of errors for cause and respond to it formally with education on why the errors occurred, compliance reviews to be sure that errors are reduced, and adjustments to practice processes as needed to prevent future errors.

“Should a RAC audit show serious errors from a practice, there is the possibility that the RAC will involve a Medicare or Medicaid program integrity contractor or the Office of the Inspector General to further audit the practice,” she says. “When this occurs, it is important to show the practice’s efforts at being educated on correct coding and billing and correction efforts in response to problems found.”

Some family medicine residency programs are adjusting their training to include documentation topics, recognizing the importance of the residents understanding how to correctly code and bill and avoid pitfalls in preparation for entering practice.

Todd Thames, M.D., program director of the Christus Santa Rosa Family Medicine Residency Program in San Antonio, says that his program holds a regular family medicine practice management lecture series on coding and billing. In addition, all of their residents do their own coding in the clinic from day one, under faculty supervision.

More important is a quarterly lecture given by an outside billing consultant on coding guidelines, reimbursement alerts, and any other changes, who afterward conducts individual meetings with each resident and faculty member to go over the results of a coding audit of his or her claims that has been generated by a third-party auditor. “It’s vital” to the training experience, Thames says.

He advises other Texas family medicine residencies to integrate coding and billing into the resident experience and build in a concurrent audit system that includes the residents so they get regular feedback on how their coding and billing compares to internal benchmarks and national benchmarks. “We tell the residents all the time, ‘we can teach you medicine until the cows come home, but if you don’t know how to keep your doors open, you can’t do the community any good.’”

As the RACs continue to produce significant results in identifying improper payments in Medicare, Reiner says there is no doubt that everyone will undergo a RAC audit sooner or later. “In almost every practice, a RAC can find some billing, coding, or documentation issue during any given audit. It is easy to make mistakes even if you have all of the right processes in place. The rules are too complex and differ from payer to payer.”

“Having a compliance plan in place and documentation training can help decrease the risk of an audit or overpayments. It is not a matter of if, but when, in regards to auditing medical practices.”

10 tips for preventing common evaluation and management coding errors

By Bradley Reiner

- The chief complaint, or CC, must be stated clearly. It identifies the medical necessity and sets the tone for the visit. A statement such as “follow up” or “comes in today” does not constitute a chief complaint. You must define why the patient is coming in to the office. Chief complaints must be documented for all levels of evaluation and management services.

- The nature of the presenting problem must be clear and stated fully in the history of the present illness, or HPI. The higher-level codes require that four or more elements be documented or you must provide a description or status of three or more chronic conditions based on the 1997 Documentation Guidelines for Evaluation and Management Services.

- A complete past/family/social history, or PFSH, is necessary for consults and new patient visits. This means that all three areas have to be documented for higher level E/M codes.

- The review of systems, or ROS, must be appropriate for the clinical circumstances. The review must be related to the nature of the presenting problem and chief complaint. Record the positives and pertinent negatives. The phrase “all systems negative” is frowned upon by the Medicare contractor. It is recommended that each system be listed separately.

- Always examine the system or systems related to the presenting problem. Use “normal” or “negative” to describe asymptomatic organ systems. “Abnormal” without elaboration is insufficient.

- Code the physical exam considering the clinical circumstances of the encounter—don’t code based on unnecessary information added for the purposes of meeting the requirements of the higher-level codes.

- Document all diagnostic tests ordered, reviewed, and independently interpreted or viewed as part of the work of the encounter.

- Medical decision-making involves the number of diagnoses and management options as well as tests reviewed and ordered, and the risk of complications. Don’t assume this can be inferred. Clarify this in the assessment and plan.

- It is unnecessary to count old diagnoses unless you can clearly demonstrate that their presence increased the work of the current encounter, or led to the complexity of the encounter.

- Beware of software for electronic medical records that count and overestimate an established code based on the number of areas listed. Medical decision-making ultimately drives code choice. An EMR may suggest a high-level code because you documented all elements in the history and exam, but if the presenting problem was for an issue as minor as a hangnail, it would be inappropriate.