Cover: Trading Volume for Value

Trading Volume for Value

Can we solve the country’s health care cost crisis by aligning payment incentives with desired outcomes in a new era of austerity?

As worry builds over the long-term prospect of escalating deficits and mounting federal debt, reforming our health care delivery system may offer the best chance of solving the nation’s health care cost crisis. Changing the way we pay for care so that physicians and other providers reap greater rewards for value than for volume could be the key to slowing inflation in health expenditures while improving the quality of care we deliver.

By Jonathan Nelson

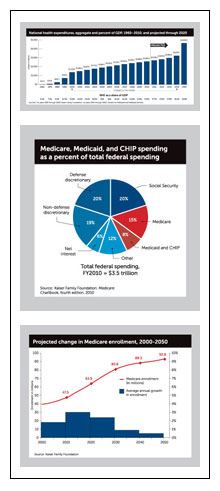

This year, total health care spending in the United States will top $2.7 trillion, exceeding 17 percent of the gross domestic product. For the past 50 years, U.S. health care spending has outpaced GDP by about 2.5 percentage points on average, and the trend shows no sign of slowing. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services predict national health expenditures will rise to $4.6 trillion and almost 20 percent of GDP by 2020.

If health care were like other sectors of the economy, such sustained increases in spending wouldn’t necessarily be detrimental. After all, the industry employs an expanding workforce and sells new technology and services to a demanding customer base, while requiring the products and services of other industrial sectors to support its growing infrastructure.

Here’s the rub: Almost half of all health expenditures are paid by government programs. Together, Medicare, Medicaid, and the State Children’s Health Insurance Program comprise about 23 percent of the entire federal budget.

In its 2011 long-term fiscal outlook, the U.S. Government Accountability Office reports that while cost-containment measures in the Affordable Care Act could “markedly improve” the country’s future deficit status, if those measures don’t succeed, 89 cents of every dollar of federal revenue will go to pay for Medicare, Medicaid, Social Security, and the net interest payments on the federal debt by 2020. With 2.8 million baby boomers becoming eligible for Medicare this year and another 75 million awaiting their turn, there is no question that the rising cost of health care is the most significant contributor to the nation’s long-term deficit.

Medicare alone makes up 15 percent of federal spending and is expected to cost $555 billion this year. By 2020, CMS predicts Medicare will cost $903 billion. Popular reform ideas for Medicare like increasing the age of eligibility and requiring richer beneficiaries to pay higher premiums would reduce federal expenditures in the program, but they don’t address the underlying problem of escalating costs. Instead they shift costs to individuals, hospital districts, and state, county and local tax bases, further straining the potential for economic development in those communities and ultimately constricting U.S. living standards.

A new study by David Auerbach and Arthur Kellermann at the RAND Corporation shows that growing health care costs have wiped out 10 years of income gains for the average American family. The authors conclude:

“Given the perilous state of the U.S. economy, the fiscal burdens imposed on all payers by steadily rising health care costs can no longer be ignored. Controlling health care spending is a defining challenge of our times.”

3 possible futures

The 75-year predictions by the Congressional Budget Office on federal spending for Medicare and Medicaid as a percentage of GDP if health care costs rise at their historical pace are so absurd as to be impossible. By definition, an unsustainable trend cannot continue, so significant reduction in the growth of health care costs is inevitable. How and when it will be achieved are the questions of concern.

Kim Slocum, board chair of the nonpartisan health policy think tank Texas Health Institute, believes transformative change will happen soon. “Looking back, 2011 will probably be seen as the year that these issues came to a head as part of the discussions about the federal budget deficit,” he says.

“There is a growing consensus that our nation may not have the luxury of waiting a decade or more for the sorts of system redesign contemplated by [the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act] and ACA. It is now quite possible that something of significance will have to occur in a much shorter time period—probably within the next five years.”

As president of the Pennsylvania-based health industry consulting firm KDS Consulting, Slocum sees three possible futures for the U.S. health care system. In the first, reforms in the way we pay for and deliver care work; we successfully deploy the tools and processes to bend the cost curve so that health care costs rise at the same rate as GDP. In that possible future, we create a more integrated system that rewards good health care outcomes and efficiency, creating value for patients and health care providers alike.

The second option involves a massive shift of health care costs to patients. Benefit packages would probably be gutted and out-of-pocket costs would soar. “A large body of health policy research shows that patients are relatively poor decision-makers about the care they need and when faced with steep out-of-pocket costs, simply stop consuming all medical services without regard to whether those services are optional or vital,” Slocum says. “The impact on the nation’s health and physicians’ practices from such an approach would be quite negative.”

In the final option, the government imposes controls on the prices of goods and services in the health care industry. “Paradoxically, this scenario is relatively popular with the general public and therefore must be considered the default future for U.S. health care if attempts to manage cost growth through the value approach were to fail.”

According to a March 2011 CBS poll, 68 percent of Americans believe the deficit is a “very serious” problem, but 54 percent think the budget can be balanced without cutting Medicare spending. A recent Harris Interactive poll shows that 59 percent oppose increasing Medicare co-pays and deductibles to shore up the program, and 50 percent oppose raising the Medicare payroll tax. Two-thirds of those polled favored cutting prescription drug prices; 44 percent favored reducing Medicare reimbursements for hospitals; 40 percent said doctors should receive lower Medicare payments.

“The three choices are before us,” Slocum says. “As one of the most powerful constituencies in health care, physicians can have an important part to play in swaying the national dialogue. It is up to the medical community to decide whether it wants to lead or follow in this important decision.”

Changing the game

So how do we bring about the first possible future for health care and avoid the other two? We have to understand what is driving inflation in health care costs, and we think we have a pretty good idea. The demand for new technology and treatments is broadly considered the most important inflationary factor. The aging of the population makes a contribution as well, as does the lack of responsibility patients bear in governing the quantity of services they consume and the cost of those services.

Two aspects of the health care system that both contribute to rising health costs and frustrate efforts to reduce that escalation are the perverse incentives inherent in the fee-for-service payment structure, and the utter lack of understanding of what it costs to provide care at the patient level. To accurately price any service, you must be able to measure the cost of resources required to provide that service. In today’s complex and fragmented delivery system, that ability doesn’t exist, and in the current payment system, there is little incentive to obtain it. To solve these two problems will require system-wide transformation and effective organizational structures that facilitate and reward clinical integration, like patient-centered medical homes, and possibly accountable care organizations.

At the sixth National Pay for Performance Summit in San Francisco, Calif., in March of this year, Harold Miller was assigned the task of describing the necessary strategies for implementing reforms in the way care is paid for. He is the president and CEO of the Network for Regional Healthcare Improvement and the executive director of the Center for Healthcare Quality and Payment Reform. He told attendees the key to achieving savings and efficiency in the health care system without rationing care is to focus on improving patient care, and to make the first order of business keeping patients well. Next, when patients do acquire preventable conditions or chronic diseases, the priority should be proper management of those conditions in a way that reduces avoidable hospitalizations. And when patients require hospitalization or experience acute care episodes, the priority must be to ensure that they don’t get infections, complications, or readmissions, and that care is delivered in the best way possible.

“The good thing is that those are all ways of saving money, but they are also ways of improving quality and outcomes for patients,” Miller said, “and I think that if we were to tell the American people that what we were trying to do is to keep them well, help them avoid having to go to the hospital, and to make sure they have a good experience when they go there, most people would say, ‘These ACO things may be pretty good deals.”

The problem is fee-for-service payment discourages such a patient-centered approach. “The current payment system pays doctors and hospitals more when patients get infections and complications. It pays them more the more often they go to the hospital, and nobody makes any money at all in health care when patients stay well.”

Across the country, health systems like Intermountain Healthcare in Utah, Geisinger Health System in Pennsylvania, Advocate Physician Partners in Illinois, and Village Health Partners in Plano, Texas, are developing cultures of value in health care rather than volume, and they are finding ways to thrive financially. Through clinical integration, measuring quality, carefully examining clinical and administrative processes, and adhering to evidence-based protocols, these systems and group practices are lowering overall health costs and improving their quality of care. Eschewing fee-for-service and implementing payment strategies that support high-quality, coordinated, patient-centered care is crucial to their success.

“Fee-for-service has only one baked-in incentive, and that is to encourage the production of services,” says François de Brantes, executive director of the Health Care Incentives Improvement Institute, or HC3I. “People shouldn’t be surprised that health care is rolling at two times [the U.S. Consumer Price Index] because the core incentive in health care is to produce more services. The core incentive in every other part of the industry is to produce more value.” Change that equation, de Brantes says, and you change the rate of health care cost growth.

De Brantes describes all payment models arrayed on a spectrum of incentives, with fee-for-service at one pole, and capitation at its opposite pole. On the fee-for service side, the payment model encourages utilization of services, favoring those services that are the most expensive. At the other pole, capitation completely discourages utilization. Over the past 40 years, the only period when health care costs didn’t rise faster than the rest of the economy was during the managed-care capitation phase of the early 1990s.

Total capitation has its problems, too. It puts physicians at risk for the level of health of their entire patient panel, so physicians in a sicker population suffer financially. “If you think about it from an economist’s perspective, capitation is a little like a retainer,” de Brantes says. “The next minute that you spend on that particular patient, you lose money. Payment reform was really born from the realization that being stuck at one pole or the other pole doesn’t make a lot of sense, and instead we ought to have these gradations, and try as much as possible to match the payment, which drives the incentive, around the services and the care for the patient that makes sense.”

Episode-of-care payments and global payments sit in the middle of the spectrum, because they encourage judicious utilization of services for each condition or each patient. Take a patient with congestive heart failure, for example. Under a fee-for-service model, if that patient has multiple acute care episodes, hospitalizations, and readmissions, each physician and hospital involved in each instance of care gets paid. The sicker the patient becomes, the more care he needs, and the more money the providers make.

Now suppose that patient’s care is paid through an episode-of-care model. All care related to the treatment of his congestive heart failure is paid out of a budget intended to cover some chunk of care—all care for his CHF over a calendar year, for example. The care team now has a real incentive to integrate their clinical data, collaborate on treatment decisions, and invest in better management of his condition. The physician assumes the risk associated with the resource costs of managing the patient’s condition during that period of time, but there’s a new budget for each patient, so there’s no incentive to avoid a new patient or a new condition.

Through his work at HC3I, de Brantes has led the development of an episode-of-care payment model called PROMETHEUS that is being tested in several pilots across the country. Before working on PROMETHEUS, he led the development of Bridges to Excellence, one of the first large-scale pay-for-performance programs, and in 2000, he was instrumental in the launch of The Leapfrog Group, an organization of employers dedicated to improving transparency and value in health care.

He began to focus his efforts on payment reform in 2004 and 2005. “It was really clear at that time that unless we changed the compensation system, we could throw as many bonuses as we wanted on docs; we could throw as many incentives as we wanted on the hospitals; it just wouldn’t make a difference, because the inherent force of fee-for-service was stopping anything else from penetrating.”

For large health systems like Geisinger, implementing a new payment structure and improving quality and efficiency by employing system-wide clinical protocols work in part because the organizational structures to manage those strategies are in place. Clinical integration among teams of primary care physicians, specialists, care management nurses, and other providers occurs under that structure.

Family physicians who don’t practice as part of a large organization will need similar tools and processes to thrive in a health care delivery system that rewards quality health outcomes and efficiency—value rather than volume. For one, they will have to be willing to collaborate with specialists and other providers to effectively manage patients’ care. They’ll need to agree among the members of the care team on some sort of organizational structure to facilitate that collaboration. And they’ll need the ability to collect, analyze, and share clinical data to properly coordinate patient care, demonstrate quality, understand the true cost of their resources, and identify opportunities to increase efficiency.

“The push toward health information exchanges, the push toward adoption of electronic medical records, those are the essential tools of clinical collaboration for individual practices that want to maintain their autonomy, but are going to be encouraged to and decide to work with other physicians on a team, even if it’s a completely virtual team, paid under the auspices of a budget that doesn’t just focus on what they’re doing individually, but on what happens to the patient across different care settings,” de Brantes says.

“I think it’s going to look a little daunting to folks who aren’t already organized in either virtual teams or real teams to try to figure out how they participate in this thing, but you know what? This is the changing world.”

The crisis in health care costs isn’t new. Since the development of health insurance as a means of financing care delivery, reform efforts have all been attempts at controlling escalating costs. From the creation of Medicare and Medicaid in the 1960s, to Nixon’s HMO legislation and Reagan’s Medicare payment overhaul, rising costs have driven reforms.

The country’s dire fiscal outlook and the threat of long-term structural deficits will force an end to the unsustainable pace of increasing health care costs at some point and in some manner. Changing the way we pay for health care won’t solve the problem by itself, but a growing number of health policy experts believe it is a necessary step in transforming the system. If we don’t succeed in making that transformation in time, the future could be quite difficult for physicians and patients alike.

“I’m concerned about the hammer that might fall in a completely arbitrary and damaging way,” de Brantes says, “but ultimately, the threat of that hammer falling might end up being the thing that wakes everybody up.”

3 Models of Payment Reform

Blended payment: Fee-for-service plus

Health care services are still paid individually according to the Resource-Based Relative Value Scale, but physicians and other providers would receive two additional payments. For each patient, they would get a per-member per-month care management fee adjusted for the severity of the patient. Then they would get a performance bonus based on quality, patient satisfaction, cost efficiency, etc.

Episode-of-care payment

Payment is made by diagnosis for a particular episode, or over a period of time for chronic conditions. The amount of the payment is based on best practices and historical data, and is essentially a budget for the treatment of that episode or condition. The physician or provider assumes the risk of the resources necessary to provide the treatment.

Global payment, or risk-adjusted comprehensive payment

Physicians and other providers receive a global payment on a monthly per-patient basis for comprehensive primary care. The payment is adjusted for the severity of each patient, and physicians receive significant bonus payments for quality, cost containment, and patient satisfaction.