Maternal mortality and morbidity in Texas

Maternal mortality in Texas

By Perdita Henry

A 2016 study published in the journal Obstetrics & Gynecology revealed a startling trend. Researchers found that maternal mortality and morbidity rates were rising all over the country but in Texas, the rates were much worse. The authors noted that historically, women only died at this rate during war, natural disasters, and severe economic upheaval. Since none of those things were taking place in the Lone Star state, researchers couldn’t say for sure why this increase was happening. From there, news outlets picked up the story. The Houston Chronicle reported that from 2011 to 2015, 537 Texas women died while pregnant or within 42 days of delivery, compared to 296 women who died from 2007 to 2010. This doubling of maternal deaths made Texas the most dangerous place to give birth in the developed world.

The rise in maternal mortality and morbidity rates in Texas began around the same time as the Texas Legislature’s devastating cuts to family planning funds in 2011. You may remember the contentious legislative session and the many efforts to exclude Planned Parenthood from the state Medicaid program. When the Legislature adjourned, the Texas Medicaid waiver program known as the Women’s Health Program — which would have matched nine federal dollars to every one dollar spent by the state — was scrapped and 280,000 women who depended on the program were left in health care limbo. Women who already had limited access to health care services found themselves pushed out of a system that provided annual well-woman exams, access to contraceptives, and family planning education.

In the numerous news articles about the maternal death rate, coverage often centered on whether the legislative cuts set us down this path. In July of 2016, the Texas Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Task Force released a report examining the deaths that occurred in Texas from 2011 to 2012. Their initial findings revealed that there was no single cause for the increase, rather there has been a perfect storm of challenges facing Texas women. Chronic health problems, mental and behavioral health issues, drug use — both legal and illegal — and a lack of access to health care before, during, and after birth have led to awful outcomes for families and communities across the state.

The task force found that black women are the most at-risk demographic, that Hispanic women have the lowest rates of diagnosed depression or mental health issues but the highest rates of postpartum suicide, and that the number of babies born in the Medicaid program addicted to opioids is rising. With this information in hand, the task force and their chair, Baylor College of Medicine obstetrician-gynecologist, Lisa Hollier, MD, continue to dig through the data, trying to identify causes and recommend changes needed to save Texas women.

“I am really grateful that we have the opportunity to continue our detailed reviews of individual medical records for the women who have died,” Hollier says. “I think in those reviews we will really focus on causes and contributing factors. We will have an opportunity to identify the likelihood of prevention for a number of these deaths and what we could identify as potential solutions.”

A perfect storm hits women’s health in Texas

The task force found that chronic health conditions were responsible for a significant portion of maternal deaths during 2011 and 2012. These conditions were often accompanied and amplified by negative social determinants of health, exacerbating the stress on expectant mothers. “I think that the task force recognizes the importance of social determinates and that, in part, is one of the reasons we were pulling deaths from a full year after the end of pregnancy,” Hollier says. “We wanted to be sure we captured all of the relevant deaths that were potentially related to pregnancy.”

Diabetes, hypertension, and obesity are common chronic conditions that are often aggravated by pregnancy. The task force looked at several issues influencing the increased rates of maternal mortality and identified cardiac events and hypertension/eclampsia as the first and third most common causes of death within one year of delivery. Of the women who died between 2011 and 2012, 20.6 percent of them died from some sort of cardiac event, while 11.1 percent died from hypertension/eclampsia.

Mental health issues played a role in many maternal deaths. In their investigation, the task force found several missed opportunities to screen expectant mothers and refer them for mental health treatment. The National Institute of Mental Health notes that people with depression have an increased risk of developing several chronic illnesses such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and stroke, and people with chronic illnesses have an increased risk for developing depression.

In the data the task force reviewed, white women had the highest rates of diagnosed mental illness including depression and black women had the next highest rates. But in the data for Hispanic women, the task force found something curious. They had the lowest rates of diagnosed mental illness, but they accounted for the highest rates of maternal deaths by suicide. How much mental illness was going undetected and among whom? According to the report: “Factors affecting likelihood of diagnosis, such as access to care, access to medical home, provider or health care system factors, care seeking behaviors, or other issues may contribute to lower prevalence of diagnosis among non-whites.”

Hollier says the task force identified significant missed opportunities for screening for behavior health problems and referral of women to treatment. “I would encourage my colleagues who are caring for pregnant and postpartum women to be sure they are screening these women for depression using a standardized instrument.” The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologist recommends that screening happens at least once during the pregnancy and postpartum period, but Hollier says patients in her practice are screened three times: at the beginning of prenatal care, in the third trimester, and postpartum.

“I would also recommend being aware of transitions in care and assisting women in those hand-offs — a hand-off from a family physician to an obstetrician during a pregnancy and then back to the family physician, or a hand-off from a pediatrician to an ob-gyn. We noticed those care transitions often put women at risk and so paying special attention to those care transitions would also be very important.”

Drug overdose was the second leading cause of maternal deaths in Texas from 2011 to 2012, with opioids accounting for 11.6 percent of those deaths. This finding coincides with the rise of prescription drug abuse and overdoses around the country.

Substance use disorder among pregnant women can be difficult to track. “Since opioids are the most commonly abused substances both in Texas and nationwide, a way to estimate the prevalence of substance use as a contributing factor to severe maternal morbidity may be to examine the rate of neonatal abstinence syndrome in newborns,” the report states. Neonatal abstinence syndrome is defined as a group of problems that occur in a newborn who was exposed to addictive opiate drugs while in the mother’s womb. In their analysis of NAS newborns, the task force found several prenatal substance abuse cases that likely would have remained undetected by medical professionals. Opioid NAS steadily increased from 2008 to 2012, which suggests that more pregnant women were using opioids.

The task force also found that unless a pregnant woman suffered an overdose, had a history of drug addiction, or was treated for a mental health issue, her dependency would likely remain unknown and untreated. Out of the 19 women using Medicaid during their pregnancies who died of drug overdoses, 14 of them died 60 or more days post-delivery, after Medicaid coverage expires.

“The Department of State Health Services will be partnering with the Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health and will be implementing the newest AIM bundle on opioid dependence,” Hollier says. “This is great news. I think it will help us address the opioid problem here in Texas and care for the women who have opioid dependence.”

So why are black women dying more often?

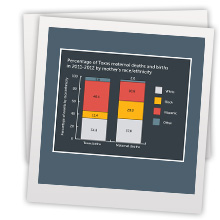

The rising mortality and morbidity rate related to pregnancy is not unique to Texas. Almost every state in the U.S. has seen a rise in maternal mortality, but one of the glaring findings researchers continue to report is the degree to which black women are affected. The task force reported that while black women only accounted for 11.4 percent of Texas births in 2011 and 2012, they accounted for 28.8 percent of pregnancy-related deaths.

We don’t know for certain why black women bear the greatest risk for maternal death, but evidence is mounting that the stress of being both black and female in America is perhaps most to blame.

Dealing with racism day-to-day is stressful. Whether you are looking for a job, shopping in a department store, or simply driving down the street, black women often have to deal with the racial biases of people they encounter. Years of continuously navigating those types of interactions takes its toll.

Arline Geronimus, a professor at the University of Michigan School of Public Health, has conducted extensive research on the ways the body is affected by continuous stress. She coined the term “weathering” to describe the cumulative impact of repeated experiences with social or economic adversity and political marginalization that may cause disproportionate physiological deterioration. “Weathering, causes a lot of different health vulnerabilities and increases susceptibility to infection, but also early onset of chronic diseases, in particular, hypertension and diabetes,” Geronimus told ProPublica.

In 2009, researchers from the University of Southern California and Harvard published a study in Social Science & Medicine, focusing on the self-reported racism experiences of both U.S. and foreign-born pregnant black women. Their study revealed that “chronic exposure to racial prejudice and discrimination could ... contribute to physiological wear and tear, thereby increasing health risk.” In several articles exploring why black women face such high maternal morbidity and mortality rates, there are recurring instances of having to deal with projections from the medical professionals charged with caring for them. Being rushed through medical processes, having their symptoms and experiences downplayed, and having to deal with snide remarks and assumptions are just some of the examples women shared with reporters about their experiences on their journey to motherhood.

Many black women must also endure the hardships of poverty, with its food insecurity, little to no access to regular health care, transportation difficulty, and the early onset of chronic health conditions. A growing body of evidence suggests black women are literally aging faster at a cellular level, and sometimes pregnancy is the straw that breaks the camel’s back.

The task force found that black women are more likely to experience hemorrhage and blood transfusion than any other race or ethnic group in the state. “This is a multifactorial problem,” Hollier says. “African-American women may be more likely to have anemia. African-American women may be more likely to have uterine fibroids, which could contribute to menstrual blood loss, which could then contribute to both anemia before pregnancy and bleeding at the time of delivery. They may be less likely to access care and get treatment for their anemia. There are many different factors that contribute to this. I imagine this is an area that will have an increase in study now that we have identified these particular disparities.”

In the meantime, the task force wants increased provider education on the impact of health disparities in health outcomes and recommends the development and implementation of programs that assist women in becoming their own advocates.

The 85th Legislature

It took a few tries, but the Legislature did take action to address this crisis. Senate Bill 17 extended the life of the Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Task Force to 2023 and added a nurse specializing in labor and delivery and a physician specializing in critical care as members. It also expanded their duties. They will now review best practices and programs of other states, evaluate health conditions and factors that affect the most at-risk population, compare rates of pregnancy-related deaths based on the mother’s socioeconomic status, and make recommendations along with the Perinatal Advisory Council to help reduce pregnancy-related death. The measure also gave the task force additional support from Health and Human Services Commission and the Department of State Health Services.

With the next legislative session scheduled for 2019, there is still much to be done and the House Committee on Public Health seems to understand that. Last fall, the committee received its interim charges from the Speaker of the House. Charge No. 1 reads:

“Review state programs that provide women’s health services and recommend solutions to increase access to effective and timely care. During the review, identify services provided in each program, the number of providers and clients participating in the programs, and the enrollment and transition process between programs. Monitor the work of the Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Task Force and recommend solutions to reduce maternal deaths and morbidity. In addition, review the correlation between pre-term and low birth weight births and the use of alcohol and tobacco. Consider options to increase treatment options and deter usage of these substances.”

With more time and more resources being dedicated to uncovering the roots of the issue, it seems like the state is on the right path.

In the end, the 2011 cuts to women’s health care certainly did not help an already vulnerable population. An increase in access to health care is necessary at every interval for women to make it through pregnancy and postpartum safely.

As the task force continues to study the rise in maternal mortality and morbidity, there has been some progress. The Texas Collaborative for Healthy Mothers and Babies in collaboration with the Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health has implemented maternal safety bundles, which will soon be available to physicians who practice obstetrics. Also, the Department of State Health Services will be participating with the Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health to implement an AIM bundle on opioid dependence.

If you would like to know more about the AIM bundles or would like more resources for yourself and your patients, check out The Council on Patient Safety in Women’s Health Care, safehealthcareforeverywoman.org/. They offer several patient safety bundles ranging from mental health to assistance in reducing peripartum racial and ethnic disparities. If you are looking for assistance in keeping your patients from losing care soon after they deliver, check out Healthy Texas Women, www.healthytexaswomen.org. There you can access toolkits on postpartum depression and Long Acting Reversible Contraceptives and much more. You can also visit The Texas Collaborative for Healthy Mothers and Babies, www.tchmb.org, which offers resources to physicians and has a significant amount of resources available to expectant women and their partners.

The road to reducing maternal mortality and morbidity is long and there is no single answer to correcting this devastating problem. Making it safer for women to begin or expand their families will take the awareness, the attention, and the time of everyone involved with bringing a child into the world.