Adolescent bone density, breast feeding, and birth control intent in the immediate postpartum period

Adolescent bone density, breast feeding, and birth control intent in the immediate postpartum period

By Sally P. Weaver, Ph.D., M.D.

McLennan County Medical Education and Research Foundation

Family Medicine Residency Program, Waco, Texas

Family medicine physicians find themselves taking care of many adolescent women who may be at risk for poor lifetime bone health. Despite a declining teen pregnancy rate, close to 400,000 adolescents ages 15-19 bear children every year in the United States.1 Unfortunately, there is little published research concerning bone health and possible risk for decreased bone mineral density, or BMD, from pregnancy for adolescents. Since the four years following menarche are a time when nearly 50 percent of adult BMD is acquired,2,3 pregnancies in adolescence may critically impact long term bone health. Adolescence is a time when young women should be experiencing skeletal growth and obtaining optimal BMD.1,3,4 Childbirth during this growth period may delay or disrupt this process and potentially decrease a woman’s peak BMD.

Bone health is a dynamic process that continues throughout a woman’s lifetime and is of particular concern for health care costs because of the significant morbidity associated with osteoporotic fractures. An estimated nearly $14 billion is spent each year taking care of health issues related to osteoporosis.5 Peak BMD correlates with the risk for osteoporosis in the postmenopausal years.6,7 High peak BMD is felt to be the most important factor in preventing osteoporosis.6 Peak BMD likely occurs in early adulthood,7-12 thus late adolescence or very early adulthood are critical time periods for maximum BMD development. Postmenopausal women who had their first child during adolescence have significantly lower BMD in their postmenopausal years.13,14 Any reductions in adolescent BMD that contribute to lower peak BMD may lead to the onset of osteoporosis at a younger age and potentially increase lifetime health care costs.

Teens are less likely to breastfeed when pregnant and have lower rates of using birth control than adult women.15-17 National statistics concerning teen contraceptive use from the Centers for Disease Control show that highly effective contraceptive methods, such as intrauterine devices or hormonal methods, are used in up to 60 percent of sexually experienced teens with the highest use among non-Hispanic whites at 66 percent.15 CDC data also demonstrates that about half of teens who become pregnant were not using any form of birth control when they conceived and only 21 percent used highly effective contraceptive methods.16

Compared to over 80 percent of adult U.S. women initiating breastfeeding, only around half of teens start breastfeeding their infants.17,18 This is important since women who breastfed during adolescence have BMD levels higher than those who had not breastfed following an adolescent pregnancy.19 The implication is that breastfeeding following an adolescent pregnancy may be protective of BMD in the long run.

This project examines changes in hip and spine BMD in adolescent women following a full term pregnancy and reports on contraceptive intent and breastfeeding initiation among postpartum teens.

Methods

To explore these issues further, we measured hip and spine BMD in Caucasian adolescents aged 14-18 years old following a full term pregnancy (n=10) and compared these measurements to never-pregnant 14-18 year old Caucasian adolescents (n=7) matched for age, BMI, and age at menarche. BMD was measured at the time of enrollment for never pregnant control subjects and at one to three weeks postpartum for pregnant subjects. Prior or current use of any hormonal birth control method was an exclusionary criterion. Data were collected concerning fracture history, tobacco and alcohol use, daily calcium supplementation, daily exercise, and personal or family history of osteoporosis. Post-menarchal age was classified into less than three years since menarche and more than three years since menarche as much of adult bone density is acquired by three years post-menarch.2-4 All postpartum enrollees were additionally queried concerning pre- and postpartum birth control use and breastfeeding intent. Recruiting for this grant supported project was much more difficult than anticipated and resulted in low numbers of study subjects.

BMD was measured at the left femoral neck, left total hip, and lumbar spine using dual-energy X-ray absorpitometry (Prodigy DXA System, Madison, Wis.). The software for this equipment is Encore 2006. All scans were performed by the same two experienced DEXA technicians. The results of these studies are expressed as a t-score (the standard deviation from the mean value of young Caucasian adult). Institutional review board approval was granted prior to subject enrollment.

For data analysis, t-tests were used to test equality of means regarding age, BMI, post-menarchal age, fracture age, and BMD t-scores. A Chi-squared test was used to test equality of proportions concerning fracture history, activity levels, and calcium use by postpartum subjects.

Results

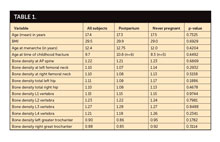

Study subjects had similar ages, BMI, and age at menarche (Table 1). Ninety percent of control and study subjects had normal for age bone density. Daily calcium supplement use was low at 10 percent among postpartum subjects and nonexistent among control subjects. There were similar rates of childhood bone fractures in both cohorts. Among the postpartum subjects, results showed a trend in lower total body bone density (combined hip and spine measurements) primarily due to lower bone density in the left hip (Table 1) Bone density in the spine did not differ significantly between the postpartum and control groups. Pre-pregnancy activity levels, BMI, fracture history, calcium use in pregnancy, and post-menarchal age were not predictors of BMD in postpartum subjects or control subjects.

Thirty percent of study subjects had been using some form of birth control prior to conception, but around 90 percent planned to use birth control after pregnancy. Seventy percent of those teens were planning on using highly effective contraception methods in the form of an IUD or a hormonal method (40 percent and 30 percent, respectively).

Concerning postpartum subjects, breastfeeding initiation rates were low at only 40 percent and very few of the teens had plans for how long they would breastfeed.

Discussion

Adolescence is a time when young women should be experiencing maximal skeletal growth and obtaining peak BMD. Childbirth during this growth period may delay this process and potentially decrease a woman’s peak BMD. This study showed a trend toward lower BMD in postpartum adolescents but is limited by the small population enrolled. It is possible that this trend would reach statistical significance in a larger study population. Additionally, the population examined in this study had high BMI scores and higher than expected t-scores in most all subjects which might obscure lesser changes in bone density. Greater efforts are needed to further analyze postpartum BMD changes in adolescents and their long term impact on peak BMD and future development of osteoporosis.

As for contraceptive use in the study population, there was a low use of birth control prior to pregnancy at 30 percent, but the study did exclude subjects with any history of hormonal contraceptive use to avoid confounding BMD findings. Including hormonal contraceptive use, approximately one half of teens nationwide were using birth control when they got pregnant.16 Postpartum subjects did report a high level of current or planned birth control use at 90 percent, compared to a national average of around 82 percent in teens not pregnant, postpartum, or seeking pregnancy.15 More study subjects were using or planned to use highly effective contraceptive methods such as IUDs or hormonal methods, compared to the national average for all teens of around 59 percent.15 Caucasian teens report a higher prevalence of highly effective use nationally at 65 percent which is fairly comparable to our postpartum Caucasian cohort.15

Limited evidence suggests that breastfeeding may be protective of long-term BMD in adolescents.19-20 Breastfeeding initiation rates in this report on postpartum adolescents were low at only 40 percent compared to a national average of around 53 percent for teens.18,21 This may be due to lack of education on the benefits of breastfeeding, family non-support, stories of negative breastfeeding experiences from peer, and/or poor professional involvement from doctors and nurses. The long-term impact of breastfeeding on a teen’s BMD is still a matter for further research.

Conclusion

Postpartum teens had lower hip BMD but this did not reach statistical significance, likely due to low numbers of subjects. Breastfeeding rates were low which may further impact long term peak BMD and future risk for osteoporosis. Many postpartum subjects were using highly effective contraceptive methods.

This small study on BMD in postpartum adolescents adds to the limited body of literature concerning bone health in postpartum teens. Greater efforts are still needed to further analyze the impact of pregnancy and breastfeeding on peak BMD and long term bone health in this population.

References

1. Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Ventura SJ, et. al. Births: Final data for 2010. National Vital Statistics Reports. 2012;61(1):1-3.

2. Sabatier JP, Guaydier-Souquieres G, Benmalek A, Marcelli C. Evolution of lumbar bone mineral content during adolescence and adulthood: a longitudinal study in 395 healthy females 10-24 years of age and 206 premenopausal women. Osteoporosis International 1999; 9(6):476-482.

3. Gordon CL. The contributions of growth and puberty to peak bone mass. Growth, Development and Aging 1991; 55(4):257-262.

4. Bailey DA, McKay HA, Mirwald RL, Crocker PR, Faulkner RA. A six-year longitudinal study of the relationship of physical activity to bone mineral accrual in growing children: the university of Saskatchewan bone mineral accrual study. Journal of Bone & Mineral Research 1999; 14(10):1672-1679.

5. Ray NF, Chan JK, Thamer M, Melton LJ, III. Medical expenditures for the treatment of osteoporotic fractures in the United States in 1995: report from the National Osteoporosis Foundation. Journal of Bone & Mineral Research 1997; 12(1):24-35.

6. Hui SL, Slemenda CW, Johnston CC, Jr. The contribution of bone loss to postmenopausal osteoporosis. Osteoporosis International 1990; 1(1):30-34.

7. Hansen MA OKRBCC. Role of peak bone mass and bone loss in postmenopausal osteoporosis: 12 year study. BMJ 1991; 303(6808):961-964.

8. Gilsanz V, Gibbens DT, Carlson M, Boechat MI, Cann CE, Schulz EE. Peak trabecular vertebral density: a comparison of adolescent and adult females. Calcified Tissue International 1988; 43(4):260-262.

9. Lu PW, Briody JN, Ogle GD et al. Bone mineral density of total body, spine, and femoral neck in children and young adults: a cross-sectional and longitudinal study. Journal of Bone & Mineral Research 1994; 9(9):1451-1458.

10. Matkovic V, Jelic T, Wardlaw GM et al. Timing of peak bone mass in Caucasian females and its implication for the prevention of osteoporosis. Inference from a cross-sectional model. Journal of Clinical Investigation 1994; 93(2):799-808.

11. Recker RR, Davies KM, Hinders SM, Heaney RP, Stegman MR, Kimmel DB. Bone gain in young adult women.[see comment]. Journal of the American Medical Association 1992; 268(17):2403-2408.

12. Teegarden D, Proulx WR, Martin BR et al. Peak bone mass in young women. Journal of Bone & Mineral Research 1995; 10(5):711-715.

13. Fox KM, Magaziner J, Sherwin R et al. Reproductive correlates of bone mass in elderly women. Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. Journal of Bone & Mineral Research 1993; 8(8):901-908.

14. Sowers M, Wallace RB, Lemke JH. Correlates of forearm bone mass among women during maximal bone mineralization. Preventive Medicine 1985; 14(5):585-596.

15. Sexual experience and contraceptive use among female teens. MMWR: Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 61(17);297-301. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr on March 4, 2013.

16. Prepregnancy contraceptive use among teen with unintended pregnancies resulting in live birth. MMWR: Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 61(02);25-29. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr on March 4, 2013.

17. Scanlon KS, Grummer-Strawn LM, Chen J, Molinari N, Perrine CG. Racial and ethnic differences in breastfeeding initiation and duration by state - National Immunization Survey, United States, 2004-2008. pp. 327–334.

18. Breastfeeding report card-United States, 2012. Centers for Disease Control, http://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/data/reportcard.htm#Rates. Accessed March 4, 2013.

19. Chantry CJ, Auinger P, Byrd RS. Lactation among adolescent mothers and subsequent bone mineral density. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine 2004; 158(7):650-656.

20. Bezerra FF, Mendonca LM, Lobato EC, O’Brien KO, Donangelo CM. Bone mass is recovered from lactation to postweaning in adolescent mothers with low calcium intakes. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2004; 80(5):1322-1326.

21. Tucker CT, Wilson EK, Samandari G. Infant feeding experiences among teen mothers in North Carolina. International Breastfeeding Journal. 2011;6(14):1-11.

Support for TAFP Foundation Research is made possible by the Family Medicine Research Champions.

Gold level

Richard Garrison, M.D.

David A. Katerndahl, M.D.

Jim and Karen White

Silver level

Carol and Dale Moquist, M.D.

Bronze level

Joane Baumer, M.D.

Linda Siy, M.D.

Lloyd Van Winkle, M.D.

George Zenner, M.D.

Thank you to all who have donated to an endowment. For information on donating or creating a new endowment or applying for research grants, contact Kathy McCarthy at kmccarthy@tafp.org.

Acknowledgement: The author would like to thank Cindy Passmore, M.A., for her assistance with statistical analysis.

Click to view chart.

Click to view chart.