What should be required to practice medicine?

What should be required to practice medicine?

By Jonathan Nelson

“Professional nursing” means the performance of an act that requires substantial specialized judgment and skill, the proper performance of which is based on knowledge and application of the principles of biological, physical, and social science as acquired by a completed course in an approved school of professional nursing. The term does not include acts of medical diagnosis or the prescription of therapeutic or corrective measures. — Texas Nursing Practice Act, Subchapter A, Sec. 301.002.

It’s no secret that Texas suffers from a shortage of primary care physicians, and that as health reform initiatives are implemented over the coming years, the demand from newly insured patients will put even more strain on the system. Nurse practitioner organizations are seizing this opportunity to demand that their members be granted the authority to diagnose and treat patients without physician collaboration, and they are receiving significant support.

Recent articles in the San Antonio Express-News and the Austin American-Statesman are just the latest of a spate of news stories touting the possible benefits of removing all requirements that nurse practitioners collaborate with physicians. This fall, AAFP had to fight openly to convince the National Board of Medical Examiners to reconsider several policy statements asserting equivalence between physicians and graduates of doctorate of nursing practice programs.

In early October, the Institute of Medicine released a controversial report, “The Future of Nursing: Leading Change, Advancing Health,” which called for states to remove scope of practice barriers on nurse practitioners. The report drew immediate criticism from AAFP, TAFP, and the American Medical Association.

“The report simply says, ‘Do away with all blocks on full scope of practice. Do away with anything that prohibits an advanced nurse practitioner from having direct patient care or direct licensing,’” said AAFP President Roland Goertz, M.D., M.B.A., in an Oct. 6, 2010, AAFP News Now story. “It doesn’t mention anything about how to maintain competencies or ensure patient safety.”

“Nursing, as a whole, is not just about advanced practice nursing,” Goertz went on to say. “In my community, the largest need from a nurse staffing standpoint is not advanced nursing degree people but bedside nursing—nursing that works side-by-side with teams of practices in the area.”

AMA board member Rebecca J. Patchin, M.D., made a similar statement on Oct. 5, 2010. “With a shortage of both physicians and nurses and millions more insured Americans, health care professionals will need to continue working together to meet the surge in demand for health care. A physician-led team approach to care—with each member of the team playing the role they are educated and trained to play—helps ensure patients get high-quality care and value for their health care spending.”

Texas is one of 34 states that require nurse practitioners to collaborate at some level with physicians if they are to engage in diagnosis and prescribing. Earlier this year, the Associated Press reported that 28 states were considering legislation that would remove those requirements.

Texas lawmakers will almost certainly consider similar legislation when the 82nd Texas Legislature convenes in January 2011. For physicians, the question of giving nurse practitioners the authority to diagnose and prescribe without physician collaboration is not a fight over turf; it is an issue of quality and safety.

Family physician Sandra Esparza, M.D., is in private practice with her husband, a pediatrician, in Round Rock. A young woman complaining of frequent urination recently sought treatment from Esparza after seeing three different nurse practitioners at a retail health clinic over as many weeks. The patient claimed that at each visit, the nurse practitioner on duty checked her urine, told her she had a urinary tract infection, prescribed an antibiotic, and said the infection should clear up in a few days. And each time, the symptoms persisted.

“She finally got frustrated because they weren’t really doing anything, so she came to see me,” Esparza says. “She had a very large dermoid tumor on her ovary, and she was such a thin young woman you could actually see it protruding from her abdomen. She was in surgery that night.”

The tumor was the size of a small grapefruit, Esparza says, and it had been pressing against the patient’s bladder causing her symptoms. Three nurse practitioners on separate occasions had missed the diagnosis completely.

In another recent case, Esparza saw a male patient complaining of pain and swelling in his cheek. He had seen a nurse practitioner at the same retail health clinic who had diagnosed him with an enlarged lymph node and prescribed a round of antibiotics. The treatment had not affected his symptoms.

“Anyone who has studied anatomy knows there are no lymph nodes in the center of the cheek,” Esparza says. The patient had a salivary gland stone, and with the application of warm compresses, the swelling was alleviated.

“These are nurses who haven’t taken full anatomy and physiology. My husband and I like to say, ‘everybody wants to be a doctor, but nobody wants to go to medical school.’”

Barbara Pierce, M.D., a family physician in College Station, tells of a recent patient who arrived at her clinic in an ambulance. The patient was a resident in a nursing home who had been seen by a nurse practitioner because pus was seeping from her ear. The nurse practitioner diagnosed the patient with serous otitis and referred her to an ear, nose, and throat specialist.

“Somehow the nursing home sent her to me instead; a little Alzheimer’s dementia lady, wheeled in on a stretcher to my office with her contractures and frantic moans,” Pierce says. With a quick glance, Pierce confirmed the diagnosis of otitis externa and prescribed antibiotic ear drops.

“If a nurse practitioner whose primary job is in a nursing home cannot treat a simple otitis externa, and sends a weak little elderly woman on a traumatic ambulance trip across town for evaluation, how can we be confident in her care of more complex issues with these often complicated nursing home patients?”

Education and training are the difference

Cases like these are why physicians question the wisdom of granting nurse practitioners the authority to diagnose and prescribe independently. Rodney B. Young, M.D., is an associate professor and the regional chair of the Department of Family and Community Medicine at Texas Tech University Health Science Center School of Medicine at Amarillo. He agrees that nurse practitioners are a valuable part of the solution to Texas’ shortage of primary care, but that the Legislature should continue to require them to practice as part of a coordinated team with appropriate physician collaboration rather than lowering the standard for the practice of primary care.

“There are many excellent clinical nurse specialists who practice surgical subspecialties such as neurosurgery and orthopedics with physicians,” he says. “Many of them are so experienced that they could practically perform some of the surgeries themselves, yet there is not a reasonable person out there who thinks that would be a good idea. Primary care is no less complicated than surgery; it’s simply different, and more cognitive than technical in most cases.”

“Pharmacy technicians can dispense most prescriptions just as well as pharmacists, but they are not the same,” Young says. “Physical therapy techs can provide many of the same treatments and modalities as the PTs themselves, but they are not the same. Paralegals know many of the same legal issues as lawyers, but they are not the same. Nurse practitioners can know a lot about primary care, but they are not primary care physicians.”

The difference is in the training. While nurse practitioners are trained to emphasize health promotion, patient education, and disease prevention, they lack the broader and deeper expertise needed to recognize cases in which multiple symptoms suggest more serious conditions. Family physicians are trained to provide complex differential diagnosis, develop treatment plans that address multiple organ systems, and order and interpret tests within the context of patients’ overall health conditions.

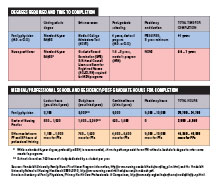

This expertise is earned through the rigorous study of medical science in the classroom and the thousands of hours of clinical study in the exam room that medical students and residents must complete before being allowed to practice medicine independently. As described by AAFP in policy documents addressing scope of practice issues, patients can depend on and expect a level of expertise and quality from doctors because primary care physicians throughout the United States follow the same highly structured educational path, complete the same coursework, and pass the same licensure examination.

There is no such standard to achieve nurse practitioner certification, as their educational requirements vary from program to program and from state to state. Nurse practitioners normally receive their education through a one-and-a-half year to three-year degree program. Some complete this education through online degree programs rather than attending an institution. According to research conducted by AAFP, during their education, nurse practitioners experience between 500 and 1,500 hours of clinical training. At the completion of medical school and residency training, a family physician has experienced between 15,000 and 16,000 clinical hours.

A 2007 study published in the American Journal of Nurse Practitioners reported that more than half of practicing nurse practitioners responding to a survey believed they were “only somewhat or minimally prepared to practice” after completing either a master’s or a certificate program.

Another survey of practicing nurse practitioners published in the Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners in 2004 showed that in the area of pharmacology, 46 percent reported they were not “generally or well prepared” for practice. “In no uncertain terms, respondents indicated that they desired and needed more out of their clinical education, in terms of content, clinical experience, and competency testing,” the authors wrote. “Our results indicate that formal NP education is not preparing new NPs to feel ready for practice and suggests several areas where NP educational programs need to be strengthened.”

Linda Siy, M.D., assistant professor in the Department of Community Medicine at the University of North Texas Health Science Center in Fort Worth, trains third-year medical students as they complete their family medicine clerkships. She points out that many of the nurse practitioners publicly making the case for autonomous practice are at the top of their field.

“They are the instructors; they are the ones with the most credentials; they are the ones with the most clinical experience,” she says. “I would probably feel comfortable sending any one of my family members to any one of them. But they’ve had the benefit of working in a system where there is physician supervision.”

These are not the nurse practitioners one should imagine when considering autonomous practice, she says. “You have to think about the nurse practitioners who have just graduated.” When a nurse practitioner completes education, he or she has about the same number of clinical hours as a third-year medical student.

“I wouldn’t trust a third-year medical student to do primary care without any supervision,” Siy says. “No way.”

Could autonomous practice by NPs save the state money?

As state officials contemplate a budget shortfall for the next biennium of between $18 billion and $24 billion, bending the health care cost curve will be a major goal of any change in health care policy in the next Legislature. Nurse practitioner organizations claim their members provide cheaper care than physicians, and that if given autonomous practice authority, they could cut state health care expenditures.

Pediatrician Ernest D. Buck, M.D., of Corpus Christi, disagrees. He is the medical director of the Driscoll Children’s Health Plan, which serves CHIP and Medicaid patients. He says in his experience, care provided by nurse practitioners is likely to be more expensive than care provided by physicians. “I do not find that the nurse practitioners are more frugal with their referrals, or that their total cost of care is cheaper than that as provided by a physician. In fact I find that they refer liberally to higher-cost specialists and to unfruitful therapies.”

Nurse practitioners perform quite well in many instances, Buck says, like when completing a Texas Health Steps well-child examination for children’s Medicaid or CHIP. “The bigger fear is when they find something abnormal, now what do they do? That’s where the expense runs up. They’re more likely to get a scan; they’re more likely to refer to a specialist or to order too much therapy.”

The American College of Physicians published a comparison of utilization rates among physicians, residents, and nurse practitioners in the journal Effective Clinical Practice, which showed that utilization of medical services was higher for patients assigned to nurse practitioners than for patients assigned to residents in 14 of 17 utilization measures, and higher in 10 of 17 measures when compared with patients assigned to attending physicians. The patient group assigned to nurse practitioners in the study experienced 13 more hospitalizations annually for each 100 patients and 108 more specialty visits per year per 100 patients than the patient cohort receiving care from physicians.

“The higher number of inpatient and specialty care resources utilized by patients assigned to a nurse practitioner suggests that they may indeed have more difficulty with managing patients on their own (even with physician supervision) and may rely more on other services than physicians practicing in the same setting,” the authors concluded.

Kim Ross, health policy consultant and owner of Kimble Public Affairs in Austin, says allowing nurse practitioners to diagnose, treat, and prescribe without any physician collaboration will only serve to further fragment the chaotic and poorly coordinated health care delivery system Texans encounter.

“Adding another independent health care provider with a billing number compounds the economic felony of rising costs with no prospect for improved outcomes or better value. It is well established from published longitudinal studies that the most effective means of bending the medical cost curve is through better care coordination in team settings, which have over time demonstrably reduced the frequency of redundant services, unnecessary referrals, and other manifestations of both under and over treatment patterns that plague Texas’ fragmented delivery systems.”

Could autonomous practice by NPs solve the state’s physician workforce shortage?

In 2009, the Texas Department of State Health Services reported that 16,830 primary care physicians were in active practice. That’s about 68 for every 100,000 people, well below the average of 81. DSHS states that 5,745 nurse practitioners were in active practice in Texas while the Coalition for Nurses in Advanced Practice says that number is more than 7,900.

Neither DSHS nor CNAP says what percentage of these practice primary care and what portion has chosen to work in other medical specialties. One recent study published in the journal Health Affairs estimates that fewer than half of all nurse practitioners in the United States practice in office-based primary care settings, and reports that 42 percent of patient visits to nurse practitioners and physician assistants in office-based practices are in the offices of specialists. Just as medical students are lured away from primary care by the prospect of more lucrative careers in high-paid medical specialties, so are nurse practitioners.

Robert C. Bowman, M.D., professor of family medicine at the A.T. Still School of Osteopathic Medicine in Arizona and noted expert on the nation’s physician workforce, reports that since 2004, the number of nurse practitioners entering primary care has dropped by 40 percent. To measure the productivity of various health care providers over their careers, Bowman designed a formula to calculate what he calls the standard primary care year. Using this measurement, Bowman found that family physicians deliver 29.3 standard primary care years over an expected 35-year career, while nurse practitioners deliver only three standard primary care years. According to Bowman, it would take almost 10 nurse practitioners to equal the primary care productivity of one family physician.

TAFP CEO Tom Banning says even if the Legislature decided to grant nurse practitioners autonomous practice, there aren’t enough of them to make a significant difference to Texas’ primary care workforce shortage and there’s no evidence to support the claim that they would practice in rural and underserved areas at a greater rate than they do today.

“You can look at the maps the American Medical Association published showing the geographic distribution of nurse practitioners and primary care physicians and see that for the most part, nurse practitioners practice in the metropolitan areas. The pattern is the same whether you’re in a state that allows independent practice or not.”

“Health care is best given in a medical team”

John Richmond, M.D., practices at what he calls a “frontline family medicine clinic” that serves a needy population in central Dallas seven days a week. He and four other family physicians practice with two nurse practitioners, one obstetrician/gynecologist, and one pediatrician, and he believes in the team-based approach to high-quality medicine.

“The breadth of knowledge, confidence, and experience of a residency-trained board-certified physician will never be matched by a NP,” he says. “However, a physician working with an NP will improve patient care and increase availability of services while also improving the knowledge, confidence, and experience of the NP. All that would be impossible if the NP was allowed to work independently without physician supervision.”

TAFP’s position on the question of whether to give nurse practitioners the authority to diagnose and prescribe independently is clear. Recently the Academy published a set of issue briefs on the subject and encouraged members to use the documents when discussing the topic with their legislators. The issue briefs, which can be found in the advocacy resources section of TAFP’s website, www.tafp.org, acknowledge that as a vital part of Texas’ health care workforce, nurse practitioners collaborate with physicians to increase access to well-coordinated medical care in communities across the state.

“Nurse practitioners and physicians have the same goal: to keep Texans healthy and productive, and to ensure that when they need it, patients have access to safe, high-quality medical care,” one brief states. “Nurses and physicians provide the highest quality health care when they work together for the well-being of their patients. They are a team, striving each day for the better health of Texans. This team should be supported and kept together by state policies that have the best interests of the patient in mind.”

“I attest that our nurse practitioners are a strong and essential part of my clinic’s success,” Richmond says. “Health care is best given in a medical team approach that combines the skills of physicians and nurse practitioners working together. The NPs need to be supervised by interested, experienced, and available physicians like myself. The current Texas medical supervision system for NPs is stable, working, and safe.”

Download Primary Care Coalition issue briefs that support arguments against granting nurse practitioners authority to diagnose and prescribe without physician collaboration on the advocacy resources page of www.tafp.org.